How to Ensure this Stability in an Era of Renewable Energy Development?

Get this executive brief in pdf format (FREE)

The blackout that occurred in Spain in April 2025 highlighted the importance of electrical grid stability in our modern societies. With the important deployment of intermittent renewable energies (particularly solar photovoltaic and wind) and the electrification of various applications, the role of electrical grids and their operators (DSOs, ISOs and TSOs) is rapidly evolving. The management of such energies is becoming more decentralised. We will examine the key technologies and parameters that allow for the integration of a large share of renewable energy into an electricity grid. We will then look at a concrete application of these technologies in Australia to understand how they could benefit other countries, such as Spain, in the near future.

The key parameters of grid stability

The stability and quality of the grid are monitored using several parameters such as frequency, voltage, and inertia:

- Frequency refers to the number of oscillations per second of electrical waves. It is set at 50 Hz for the European grid and must be kept within a tight tolerance (+/- 0.05 Hz or 0.1%) in order to avoid grid imbalance and associated load shedding or blackouts.

- Voltage determines the energy transfer capacity through the grid, with levels ranging from 220 V to 400 kV.

- Inertia defines the ability of an electrical grid to resist changes in frequency.

Traditionally, inertia is provided by large rotating machines, such as alternators from electric power plants (coal, nuclear, and gas). These machines, due to their mass and rotational speed, store kinetic energy. When electricity demand suddenly increases or decreases, this kinetic energy is released or absorbed, helping to stabilise the grid frequency.

With the increase in electricity production from renewable sources like wind and solar, which do not provide any inertia compared to traditional generators. So managing electric grid inertia becomes more complex and requires solutions such as:

- Synchronous Condensers

- "Grid-forming" Batteries

- Flywheels

- And more.

These technologies can help stabilise the frequency by quickly injecting or absorbing energy, known as "synthetic inertia." Control is more diffuse in this case, shifting from a few large power plants to dozens of inverters.

Interconnection between grids is also a key parameter to ensure the stability of the electrical grid. This article will not go into such details.

Synchronous condensers are large synchronous rotating machines, without load but similar to power plant turbines. They are coupled to the grid and synchronised to its frequency. They can either provide or absorb reactive power from the electrical grid, thus regulating voltage and improving the power factor. Additionally, flywheels can be used, which store energy in the form of kinetic energy by rotating a rotor at high speed. As such, they can be used for frequency regulation.

"Grid-forming" batteries are systems composed of batteries and inverters connected directly to the electrical grid, capable of generating their own signals in the form of specific frequency and voltage waves.

We have thus seen the main technologies available to ensure the stability of a grid with few thermal power plants.

The example of the state of South Australia

The networks most constrained by the significant development of renewable energy worldwide are California, the United Kingdom, Ireland, Spain, Australia, and to some extent, Germany. We have decided to focus our analysis on Australia, which is deploying cutting-edge solutions to face this development.

Indeed, the technologies described previously are widely prevalent in Australia, where many "grid-forming" battery projects are already operational (Source: PV magazine), and others of large size (up to 500 MW/1GWh) are under development (Source: Neoen). This deployment is enabled by several factors:

- Grid codes specifying connection modalities (Sources: AEMO-1, AEMO-2)

- Implementation of remuneration mechanisms like the large-scale battery storage funding

- Tenders for the purchase of Specific synchronous condensers (a.k.a. “syncons”)

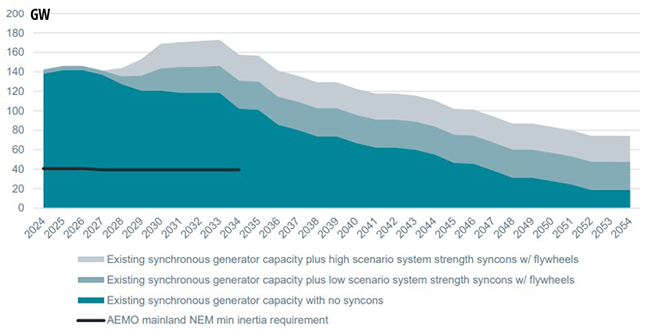

In parallel, the main Australian electrical grid, NEM (National Energy Market), managed by AEMO (Australian Electricity Market Operator), has planned the installation of synchronous condensers to compensate for the closure of existing thermal power plants. This should allow maintaining an acceptable level of inertia for grid stability by 2050 (see graph below).

Figure 1: Projected mainland NEM inertia capacity (GW) per year

Source: HoustonKemp, Evaluating market designs for inertia services

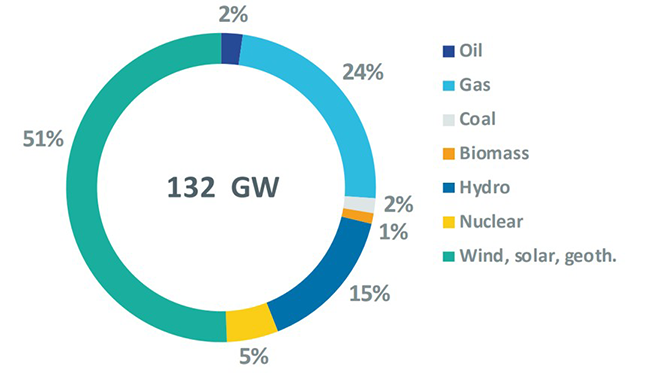

In 2023, the state of South Australia was powered by nearly 73% intermittent solar and wind energy, and served a consumption of about 15 GWh (Source: Australian gov). There is not any more base load production in this state, and gas plant are used as peaking power plants. Although one might assume that the grid stability mentioned earlier is not ensured in this state, but this is not the case. According to the latest report from the Australian market operator AEMO, it is, on the contrary, the Australian state with the safest grid. In addition to grid-forming inverter systems, four synchronous condensers have been installed in this state (Source: Renew).

Australia, a Case Study to Prevent Blackouts?

The question arises of the technical possibility of having stable electrical grids on a larger and interconnected scale, such as in Germany or Spain, with intermittent renewable energy rates of respectively 43% and 42% (Source: Enerdata, Global Energy and CO2 Data).

We can see from this case study on Australia that intermittent renewable energies are not necessarily synonymous with grid instability and/or blackouts.

So what cause the black-out in Spain in April 28th 2025? Based on the preliminary government report (Source), we can identify first explanations about the chain of events that caused the nation-wide blackout. It evokes cascading events that caused atypical voltage oscillations, with notable frequency variations. This imbalance caused several disconnections of electricity production and consumption plants, leading to the blackout. Among these events were changes in the capacity availability of interconnections with France and Portugal, unavailability of thermal power plants, deviations in reactive energy absorption in the south and centre region, and the disconnection of renewable energy plants due to overvoltage at three transformation stations. There is therefore no obvious link with intermittent renewable energies (Source: Gobierno de Espana). The information shared here should be considered in light of the fact that detailed reports by ENTSO-e and REE on the event analysis has not yet been published. Therefore, the information remains incomplete. Additionally, the factor of human error should not be overlooked in the incidents related to this event.

As mentioned before, in 2024, Spain saw nearly 42% of its electricity production provided by solar and wind energy (Source: Enerdata, Global Energy and CO2 Data), and in April 2025, a peak of 73% was even observed (Source: PV Magazine), a week before the blackout.

Unlike Australia, the solutions to improve grid inertia are not developed or barely on the Spanish continental electrical grid. There are currently no synchronous condensers in continental Spain (Source: CREA) and very few grid-connected battery projects - only 5 projects for a few tens of MW operational in 2024 (Source: Enerdata, Power Plant Tracker). To remedy this, the Ministry for the Ecological Transition and the Demographic Challenge (MITECO) has allocated, at end of 2024, 100 million euros to help the development of 35 battery projects totalling 690 MW/2.8 GWh with operation planned in 2025 and 2026 (source: PV Magazine). The use of grid-forming inverters is not mentioned. Similarly, synchronous condensers have been installed, but on Spanish archipelagos (Canarias and Baleares), not on the mainland.

Spain and its historical grid operator, Red Eléctrica de España (REE), are progressively changing their grid stability management and can draw inspiration on Australian experiences.

Conclusion and Outlook

As shown by the Spanish case, electrical grids are a major challenge in the current energy transition. In addition to the new technologies to be installed, significant efforts are needed in regulatory and market aspects to promote the emergence of new flexibilities at the local level and in demand.

Progress is being noted in this regard at the European level with the harmonisation of frequency management mechanisms (PICASSO Project, Source: Entso-e). However, the maturity level of countries on these subjects remains very heterogeneous. Enerdata works and actively monitors the development of various flexibility mechanisms in Europe to follow the best practice.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Technologies such as synchronous condensers, "grid forming batteries," and flywheels enable the management of electrical grids with high deployment rates of renewable energy.

- Electrical grids, such as the one in South Australia, are capable of operating without base load power and with an average intermittent renewable energy rate of over 70%.

- The Spanish blackout of 2025 cannot be directly attributed to renewable energies, but Spain will need to accelerate ongoing changes in the management of its electrical grid, taking, for example, cues from Australia.

Energy and Climate Databases

Energy and Climate Databases Market Analysis

Market Analysis