Affordable, reliable, and clean electricity: A complex balance to find

Get this Excutive Brief in pdf Format (free)

There has been a persistent dilemma in Southeast Asia’s energy sector: affordability vs. sustainability. Affordability has largely been the priority until now. Yet, sustainability can now rhyme with affordability, particularly in the power sector, which is a critical area for decarbonisation in ASEAN. Over the past few years, renewable energy has become increasingly cost-competitive and efficiency improvements have been made.

However, decarbonising the power sector is far more complex than simply replacing a boiler with a wind turbine or a solar panel. The power sector in Southeast Asia is not only rapidly evolving but also among the most challenging to decarbonise. It is not just a technical or economic issue, but a multi-dimensional challenge that involves energy shift, government incentives, complex power markets, and a long-term vision. While there are numerous opportunities, overcoming these challenges will require policy actions, substantial financing, and strong regional collaboration.

This report analyses some of the key challenges facing the power sector in ASEAN.

SHIFTING AWAY FROM COAL WHILE MAINTAINING AFFORDABILITY

Power generation is deeply dependent on coal

Despite growing interest in renewable energy, coal remains the backbone of electricity generation in much of Southeast Asia. The region’s power sector is still heavily shaped by affordability concerns, energy security priorities, and the legacy of fossil fuel investments.

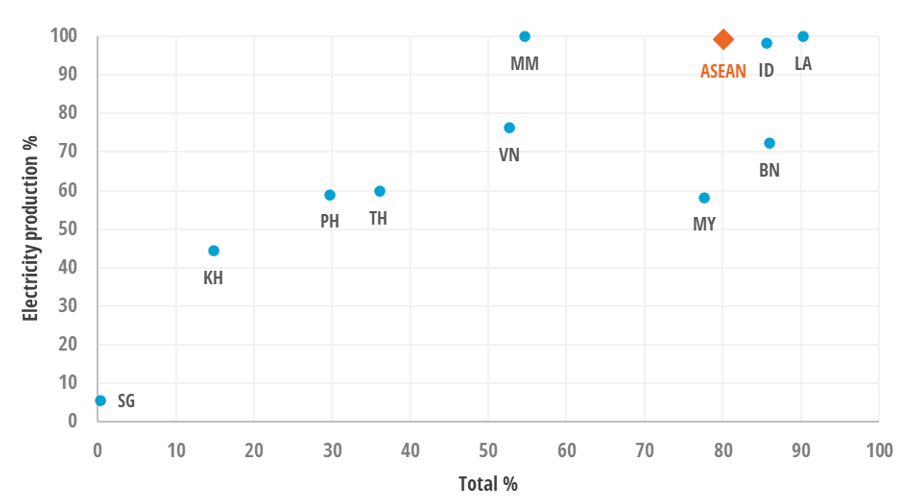

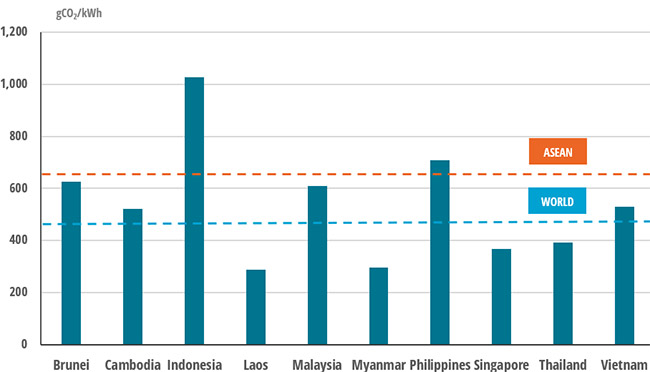

Indonesia’s coal-fired power capacity has doubled since 2015, making its electricity sector one of the most coal-dependent globally. In 2023, coal accounted for 67% of Indonesia’s electricity generation, up from 45% in 2010, resulting in a carbon intensity of 1,025 gCO₂/kWh—among the highest worldwide. Five ASEAN countries rely on coal for more than 40% of their power production. All countries combined, 44% of the electricity produced comes from coal in the region, with electricity-related CO₂ emissions rising 60% since 2015.

Figure 1: CO2 intensity of electricity generation - 2023

Source: Enerdata - Global Energy & CO2 data, Power Plant Tracker

Moreover, Southeast Asia’s coal plant fleet (totalling around 106 GW) is not only large but relatively young, averaging under 15 years old. This significantly complicates the early retirement of the plants, both economically and politically. Coal’s affordability has long supported industrial growth, particularly in Indonesia. Transition barriers include long-term PPAs, captive coal plants, and low tariffs. Vietnam faces similar challenges due to financing delays, grid constraints, and uncertainty over affordable alternatives.

Across the region, coal’s dominance is reinforced by subsidies, regulated pricing, and weak grid flexibility. Even countries with active renewable plans, like Thailand and Malaysia, continue to rely on coal for energy security and price stability. Phasing out coal in ASEAN will require not just plant closures, but structural reforms in electricity markets, smarter subsidies, regional power trade, and strong policies for renewable integration and storage.

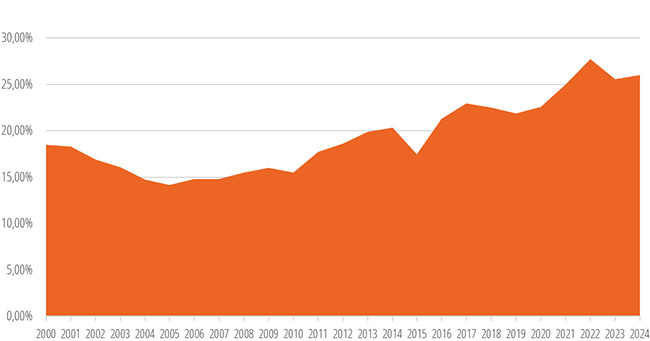

Scaling renewables thanks to better cost-competitiveness

The declining cost of renewable energy is unlocking significant potential for Southeast Asia’s power sector. Vietnam, for instance, saw its solar capacity jump from 4.9 GW in 2019 to 17 GW in 2023.

Across ASEAN, solar and wind energy now offer some of the lowest Levelised Costs of Electricity (LCOE). For solar PV, LCOEs range from US$64 to US$246/MWh, with Vietnam achieving some of the lowest costs in the region. Wind power likewise presents significant potential. Hydropower remains a crucial renewable source, particularly in Laos, where it has historically accounted for more than 80% of the country’s electricity generation. Globally, the LCOE for hydropower averages around US$48/MWh, making it an attractive option for baseload generation, though it faces challenges related to water variability and environmental concerns.

Despite the progress, several structural barriers remain. Additionally, grid infrastructure in many ASEAN countries remains underdeveloped for integrating variable renewable sources like solar and wind. Investments in grid flexibility, energy storage, and digital infrastructure are essential to fully harness renewable potential.

Figure 2: Share of renewables in the power mix of ASEAN region

Source: Enerdata - Global Energy & CO2 data, ASiANPOWER

What about nuclear and bioenergy?

As ASEAN countries seek to diversify their energy mix and reduce dependence on fossil fuels, nuclear power is emerging as a potential solution to meet growing energy demands while reducing carbon emissions. Several nations in the region, including Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and Singapore, are exploring nuclear energy as a reliable and low-carbon option. However, these projects face safety considerations and low public acceptance, while requiring strong expertise and regulatory framework.

In parallel, biomass is gaining recognition as a viable renewable energy source for power generation in ASEAN. The region's abundant agricultural and forestry residues present a significant opportunity to generate electricity through biomass-based power plants. Biomass can help mitigate waste disposal issues while providing a steady, renewable energy supply. Countries like Thailand, Malaysia, and the Philippines are already harnessing the potential of biomass, particularly for off-grid solutions and small-scale power generation. Thailand already produces 10% of its electricity from biomass.

CREATING INCENTIVES TO FINANCE THE TRANSITION

Carbon pricing and taxation

With the exception of Myanmar, Cambodia, and Laos, all ASEAN countries have included carbon pricing mechanisms as part of their climate change policy. However, only Singapore and Indonesia have implemented a national carbon price scheme to date.

Singapore has established itself as a regional leader in carbon pricing, introducing a carbon tax in 2019 set at S$5 per tCO2e. This tax is scheduled to increase to S$45 by 2026, with a potential rise to S$80 by 2030, aligning with the country's climate objectives. Other ASEAN countries are exploring similar measures. Indonesia, on the other hand, has introduced a carbon tax set at IDR 30,000 per tCO2e starting in 2024, alongside an Emissions Trading System (ETS). The ETS, mandatory for coal-fired power plants over 100 MW, aims to cut 36Mt of CO2 emissions by 2030.

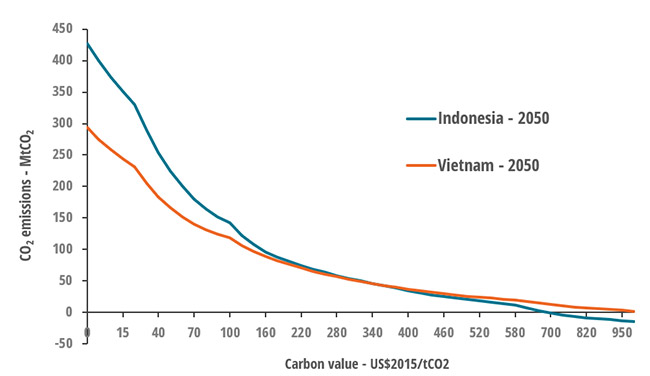

The Marginal Abatement Cost Curve (MACC) presented below shows a major impact of imposing a carbon price on the level of emissions. For instance, a value of around US$50 per tCO2 would contribute to halving emissions from the power by 2050 in Indonesia and Vietnam.

Figure 3: MACC from electricity generation – EnerBase scenario*

Source: Enerdata, EnerFuture MACCs - *Scenario definition in Appendix in the pdf

Government subsidies and international fundings

ASEAN countries are leveraging a combination of subsidies, tax incentives, and innovative financing mechanisms to support the renewable energy transition. Countries like Thailand, Vietnam, and Indonesia offer subsidies and tax incentives, including reduced import duties on renewable energy equipment. These initiatives aim to make renewable energy projects more financially attractive and reduce initial capital costs. As an example of successful policy, Vietnam implemented a generous feed-in tariff for solar users in 2020, allowing them to sell surplus power to the national grid at a price guaranteed. The policy led to 9 GW of rooftop solar installations in a single year.

In addition to subsidies, ASEAN countries are adopting blended finance models that combine public and private capital. For instance, the ASEAN Centre for Energy advocates for Project Preparation Facilities (PPFs) to support early-stage renewable energy projects. Furthermore, green bonds and other sustainable finance instruments are gaining traction in the region. Singapore, for example, plans to issue sovereign green bonds worth up to S$2.5 billion to fund environmental projects.

Finally, Indonesia and Vietnam have committed to reducing coal dependency through Just Energy Transition Partnerships (JETPs), backed by international climate finance. The program aims to provide financial and technical assistance to reduce carbon emissions and promote renewable energy. However, JETP faces significant obstacles, including financing gaps and governance challenges. The U.S. recently withdrew from its commitment to JETP, leaving a funding shortfall. While other international partners like the EU and Japan remain committed, the U.S. exit underscores the vulnerability of climate financing to political shifts.

MARKET LIBERALISATION

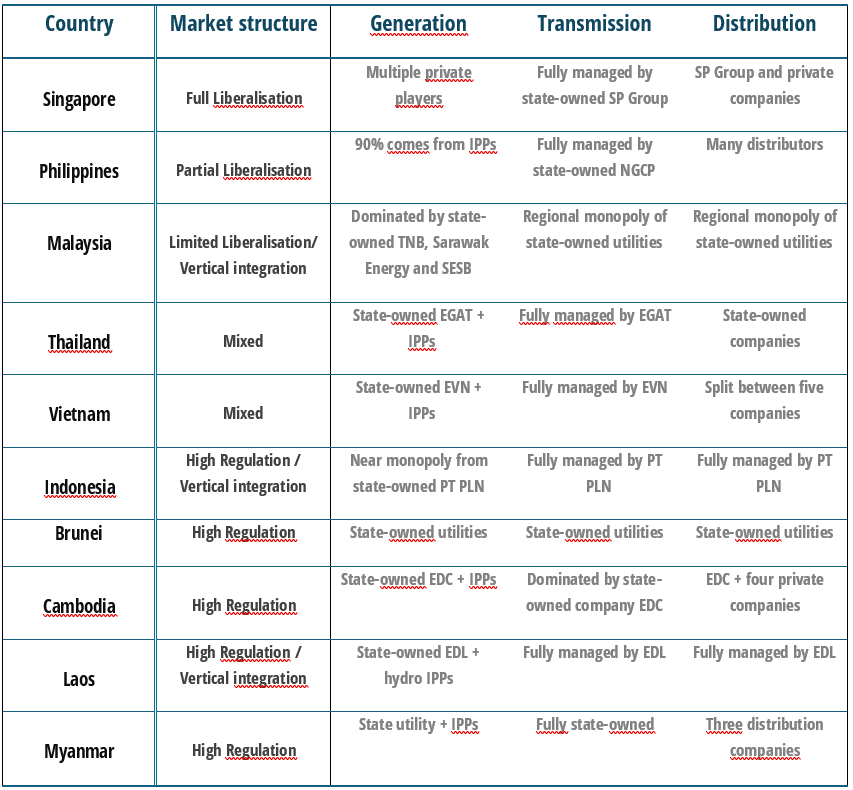

Electricity market liberalisation is a key enabler of ASEAN’s energy transition, yet progress across the region remains uneven. Only Singapore and the Philippines have implemented a competitive market structure (Singapore with full wholesale and retail competition, and the Philippines with wholesale and partial retail competition). Vietnam is advancing reforms, having launched a wholesale market and planning for retail liberalisation.

Most ASEAN countries still rely on vertically integrated, state-owned utilities controlling generation, transmission, and distribution. This restricts competition, hinders private investment, and complicates renewable energy integration and regional power trade.

More liberalised markets would support decarbonisation by enabling transparent pricing, open grid access, and flexible dispatch. It is critical for integrating variable renewables and encouraging demand-side participation. However, persistent barriers across the region include limited grid unbundling, weak regulatory frameworks, and non-cost-reflective tariffs, all of which limit the scalability of clean energy deployment and stifle innovation.

Table: Electricity market structure

Source: Enerdata - Global Energy & CO2 data

ENERGY SECURITY

Energy security remains a pressing and complex challenge across Southeast Asia as the region grapples with rising electricity demand and growing dependence on global energy markets. In Thailand, declining domestic gas output has led to a sharp rise in LNG imports exposing the country to international price volatility, as seen during the 2022 energy crisis. Vietnam faces similar risks, with delays in domestic gas development forcing it to turn to LNG amid increasing demand. In Indonesia, although coal and gas reserves remain substantial, aging upstream assets and logistical bottlenecks, especially in remote islands, strain internal supply reliability. The Philippines is particularly vulnerable, with over half of its power generation reliant on imported fossil fuels and no strategic reserves, making it highly exposed to price shocks and global supply disruptions.

Smaller states also face distinct challenges. Singapore, nearly 100% dependent on imported gas, is investing in regional interconnectors and solar, but space constraints limit domestic options. Cambodia and Myanmar continue to struggle with inadequate generation capacity and weak infrastructure, while Laos is overly reliant on hydropower exports, leaving it exposed to climate variability. Each ASEAN country faces different energy security challenges. Altogether, strengthening Southeast Asia’s energy security will require accelerated deployment of renewable energy, investment in strategic fuel reserves and grid infrastructure, and stronger regional cooperation to reduce overreliance on volatile global energy markets.

SUPPLY-SIDE EFFICIENCY – FROM PLANTS TO CONSUMERS

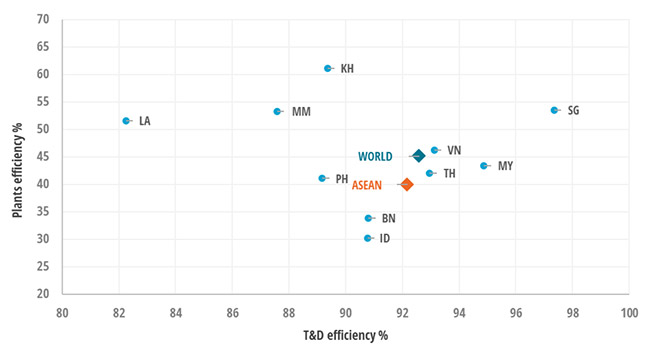

Improving the efficiency of power generation and delivery systems is essential to meeting ASEAN’s growing electricity demand while minimizing costs. On the generation side, many countries still rely on aging, subcritical coal and gas-fired power plants. The thermal efficiencies range from only 30–35%, below the global average for high-efficiency and low-emissions technologies, which can reach as high as 45%. In Indonesia and the Philippines, subcritical units dominate the coal fleet, while modern ultra-supercritical technology has been deployed only marginally. Gas-fired power plants, especially in countries with subsidised domestic gas like Thailand and Malaysia, also show wide efficiency disparities due to a mix of open-cycle and combined-cycle units. The slow turnover of aging assets and limited incentives for efficiency upgrades are key challenges.

Figure 5: Power supply efficiency indicators (2023)

Source: Enerdata - Global Energy & CO2 data

Improving the grid to optimise transmission

Transmission and distribution (T&D) losses further exacerbate supply-side inefficiencies. Average T&D losses in ASEAN hover around 9%, significantly higher than the OECD average of 6–7%. Myanmar, Laos, and the Philippines report some of the highest losses in the region, exceeding 15% in some years, largely due to underinvestment in grid infrastructure, outdated technology, and weak maintenance regimes. These inefficiencies not only increase operational costs but also undermine reliability and limit the capacity of grids to absorb variable renewable energy.

Addressing these issues requires a dual approach: first, accelerating the replacement or retrofitting of inefficient thermal plants through regulatory mandates, carbon pricing, or targeted public-private investment mechanisms; and second, modernising grid systems via smart grid technologies and high-voltage transmission projects.

Regional connectivity to foster efficiency and reliable supply

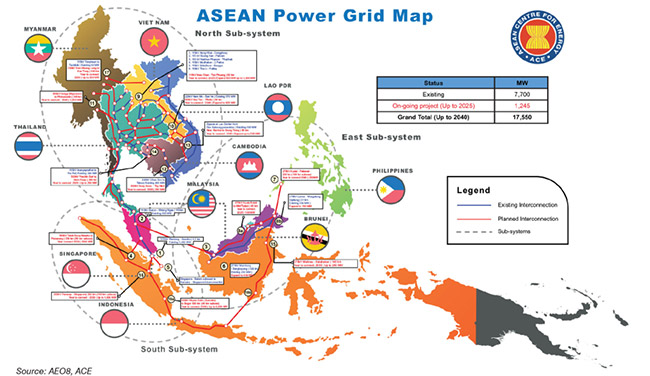

Cross-border energy trade is key, as it allows infrastructure to be built where they are the most efficient.

The ASEAN Power Grid initiative (APG) is a massive plan envisioned to foster regional energy trade. It aims to enhance energy security through cross-border power grid connections, although challenges persist due to differing readiness levels among states and limited market liberalisation.

The Lao PDR-Thailand-Malaysia-Singapore Power Integration Project (LTMS-PIP), which began operations in June 2022, has been recognized as a model for multilateral power trade. Recently, the LTMS-PIP entered Phase II, doubling electricity trade to 200 MW following an agreement between Singapore and Malaysia to import 100 MW. As of October 2024, nine out of the 18 key interconnection projects outlined in the APG have been completed, contributing to a total installed regional electricity capacity of 7.7 GW. This includes 4.7 GW from dedicated independent power producer (IPP) generation exports to the grid. Most of these interconnections are bilateral, with energy trade facilitated through long-term power purchase agreements. The extension plan is focused on increasing integration to move from bilateral trade to an interconnected network. Ongoing projects at various stages of development include subsea cables linking the Indonesian island of Sumatra with Peninsular Malaysia, overland grids connecting Kalimantan and Sabah, and upgrades to the interconnections between Thailand and Malaysia.

Figure 6: ASEAN Power Grid initiative – Projects map

Source: ASEAN Centre for Energy

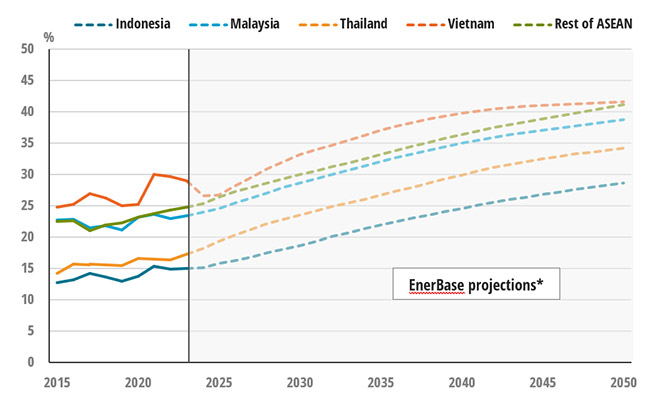

ELECTRIFICATION IN PROSPECTIVE SCENARIOS

The EnerBase projections show a steady but uneven rise in the share of electricity in final energy consumption across ASEAN countries through to 2050. Vietnam leads the region, with electricity expected to make up nearly 45% of final energy use by mid-century, reflecting its rapid industrial growth and strong uptake of renewables. Malaysia and Thailand follow, reaching just above 35%, barely aligning with their respective carbon neutrality targets for 2050 and 2065. Indonesia, however, lags behind with electricity’s share expected to stay below 30%. This slow pace is concerning given its heavy reliance on fossil fuels and its net-zero pledge for 2060. Without a faster shift to electricity in key sectors, Indonesia may risk falling short of its climate goals. The rest of ASEAN, including countries like the Philippines and Laos, are projected to have a share of electricity converging toward 40% by 2050 in a business-as-usual scenario.

Figure 7: Share of electricity in final energy consumption

Source: Enerdata, EnerFuture - *Scenario definition in Appendix

Overall, while electrification is rising, the projected figures (mostly below 45%) suggest that ASEAN is not on track to meet its long-term decarbonisation targets without more aggressive policy action, particularly in transport and industry. Hence, the big challenge is to decarbonise both the supply through clean power and the demand by electrifying consumption across sectors.

KEY TAKEAWAYS

- Coal remains dominant in ASEAN power generation, especially in Indonesia, where it accounts for 67% of electricity generation. Carbon intensity in the ASEAN power sector is among the world’s highest. Phasing out coal is difficult due to young plant ages, long-term contracts, and economic constraints tied to affordability and energy security.

- Renewables are becoming more cost-competitive, with solar and wind offering some of the lowest LCOEs. Vietnam has led the way with rapid solar growth since 2019.

- Carbon pricing is gaining traction, with Singapore and Indonesia already having a defined scheme. However, broader implementation across ASEAN is still limited.

- Electricity market reform is uneven, with only Singapore and the Philippines having a competitive market on both generation and retail. Most ASEAN power systems remain state-dominated and vertically integrated, discouraging competition and investments.

- Energy security is fragile, with countries facing rising import dependence, infrastructure constraints, and vulnerability to global energy price shocks such as LNG price.

- Efficiency gaps persist in both generation and grids with high transmission losses. Grid limitations hinder renewable integration, requiring investments in flexibility, storage, and digital infrastructure to manage intermittent sources. Regional projects like the ASEAN Power Grid show significant promise for better connectivity and reliability in the future.

Energy and Climate Databases

Energy and Climate Databases Market Analysis

Market Analysis