See also

Security, vulnerabilities and resilience in the face of growing uncertainties

Get this executive brief in PDF format

How to accelerate the EU energy transition: the power of sufficiency?

Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in February 2022, and the attacks it carried on Ukrainian energy infrastructure, have put the resilience of the European electricity transmission networks back at the centre of concerns for Europe. As a strategic element of national security, the electricity grid has again become a physical target, notably since the beginning of the 21st century, and is widely affected by cyber threats. It plays a crucial role in the dynamics of the energy transition underway in the EU and is subject to profound technical and design changes that affect its vulnerability.

The context in which these networks are managed has also changed significantly since the early 1990s. In the EU, the integration of networks, the energy transition and the electrification that it entails, as well as digitalisation and the effects of climate change, have transformed the vulnerability of the European electricity transport architecture. These transformations are taking place in a context of interdependence where the borders of electrical Europe are not necessarily those of political Europe. These changes bring about the issue of the resilience of the European grid in the face of new and diverse threats.

Key elements to understanding the European power network

Technical basis

Since the 1990s, European Union (EU) members have been pursuing a policy of integrating energy networks and markets, which has led to the widespread development of power interconnections between states. The current objective is to ensure their development is in such a way that each state can exchange a minimum of 15% of its electricity production with its neighbours. This interconnection and interdependence of networks has led to an increase in the number of European-level players who manage them. These actors' range across EU institutions, States, power producers, distributors and electricity network managers.

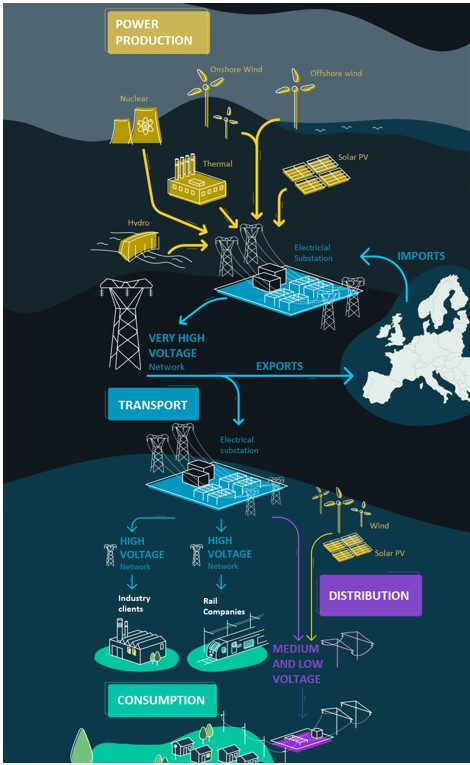

The EU's current energy transition policy is pursuing the integration of new renewable sources to produce power, and the nature and scale of this policy modifies the architecture of the European electricity transmission network. Production from these new sources, which must be integrated to the network, is often intermittent and poorly controllable due to their nature. Production is provided by both large infrastructures such as wind and solar parks, but also by smaller individual infrastructures integrated into the distribution network (low voltage), rather than into the European transmission network (high voltage).

The majority of the European transmission network transmits electricity in alternating current (AC), characterised by its frequency (the rotation of an alternator). Compared to transmission by direct current (DC), AC allows for an easier voltage conversion (from low to high or vice-versa), done via transformers. However, DC shows less power loss at high voltage and is often preferred for transmission over long distances outside Europe.

The frequency of the European network must always be maintained to ensure supply. This implies the need for a very fast response in the event of an incident and a risk of a “cascade” effect, as the European network is widely interconnected. European standards attempt to prevent these cascade effects by the so-called N-1 rule, which implies that any network infrastructure must be redundant at least once. In other words, at least two network elements must be “lost” for the supply to be threatened.

Figure 1: Schematic operation of a European electrical network

Source: RTE

Evolution of the European network

The borders of Europe’s electrical network do not necessarily follow those of political Europe. The association of European Network of Transmission System Operators for Electricity (ENTSO-E), which manages the development and interconnection of electricity markets and networks in Europe, includes 39 members representing 35 countries.

ENSTO-E includes five synchronous1 zones, resulting from the history of network construction across Europe, following the progressive control of submarine cable technology and adaptation to differences between the former USSR electricity network and that of the EU under construction.

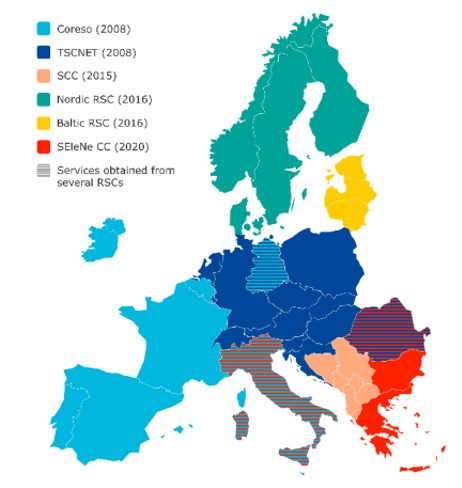

Figure 2: Regional coordination centres of the European power transmission network

Source: ENTSOE-E, 2024

The entry of the Baltic countries into the EU in 2004 was thus followed by significant investments in interconnections aimed at "disconnecting" them from the IPS/UPS network of the former USSR and connecting them to European networks and markets, thus limiting their dependence on Russia.

Network meshing allows economies of scale, solidarity mechanisms and a reduction in dependence on external imports by diversifying the mix and sources of supply. However, it increases “domino effects” in the event of an incident. To address these vulnerabilities, national network managers and ENTSO-E have been setting up regional coordination centres since 2015, which are now mandatory.

The European electricity market architecture

Simultaneously to the development of electricity networks, interconnections and renewable generation, the EU has committed to a process of opening electricity markets. This process responds to competitive logic and is applied to retail and wholesale markets. The operation of wholesale electricity markets is intertwined with the management of interconnections and security of the electricity system. The European wholesale electricity market consists of different zonal markets and different segments based on maturities:

• Futures markets (with maturities of up to several years): products traded through over-the-counter (OTC) contracts between operators or via stock markets such as EEX.

• Spot markets, operated by electricity markets: physical electricity exchanges take place one day (Day-Ahead) or a few minutes (Intraday) before physical delivery.

• Balancing markets and reserve mechanisms, operated by network operators for energy exchanges on very short notice.

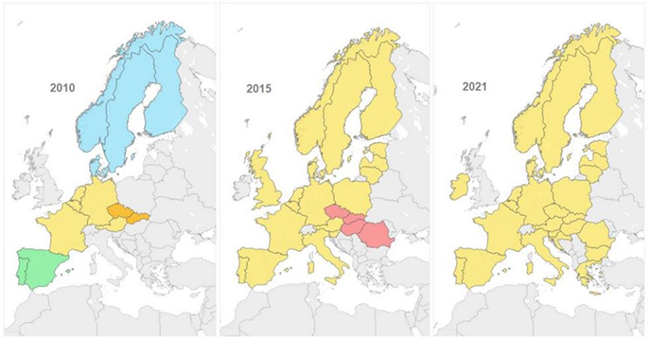

Each country has its own market infrastructures, but it is worth noting the dominant position held by the German EEX market on futures markets and the EPEX SPOT market (a subsidiary of EEX Group) on Day-Ahead trading. The French market was first coupled with Benelux in 2006, then in 2010 with Germany. In 2014/2015, the coupling was extended to Spain, Italy and the UK (which later left following Brexit). The markets are now coupled in 26 European countries.

Figure 3: Evolution of the coupling of daily wholesale electricity markets in the EU

Source: ACER, 2022

Key data on the European network

According to ENTSOE-E, the number of cross-border interconnection lines as of end-2023 amounted to 341 (304 AC lines and 37 DC lines) for a circuit length reaching 547,901 km (532,414 km in AC and 15,487 km in DC).

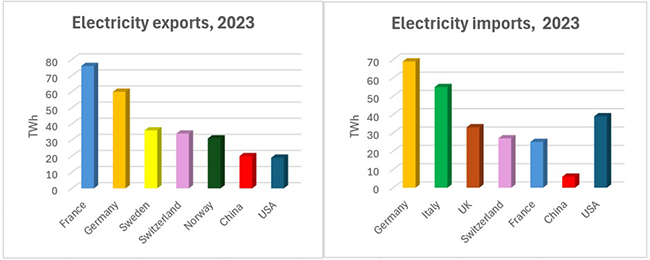

According to Enerdata, in 2023, electricity production in Europe2 reached 3,688 TWh (with 2,748 TWh for the European Union). The biggest producers were France (527 TWh), Germany (513 TWh), Türkiye (324 TWh), the UK (284 TWh) and Spain (282 TWh). In 2023, France was also the largest exporter of electricity (76 TWh), followed by Germany (60 TWh), Sweden (36 TWh), Switzerland (34 TWh) and Norway (31 TWh). Those countries are in a situation of surplus. As for the biggest importers, they were Germany (69 TWh), Italy (55 TWh), the UK (33 TWh), Switzerland (27 TWh) and France (25 TWh). The UK and notably Italy are in a situation of power deficit. In 2023, Europe transported 4,190 TWh of electricity (3,156 TWh for the EU) and distributed 2,855 TWh (2,130 TWh for the EU).

To put these numbers into perspective, China’s power generation reached 9,456 TWh and the US’ stood at 4,520 TWh in 2023, more than Europe. However, China and the US both exported only around 20 TWh, less than several European countries. In addition, China imported only about 6 TWh in 2023, while the US imported 39 TWh. This is naturally explained by the fact that Europe’s many independent power systems are tightly interconnected, whereas China and the US both are a single state, and power exchanges between US States or Chinese provinces are not taken into account. However, this data shows the extent of power exchanges inside Europe.

Figure 4: Top exporters and importers in Europe, compared with China and the US

Source: Enerdata, Global Energy and CO2 data

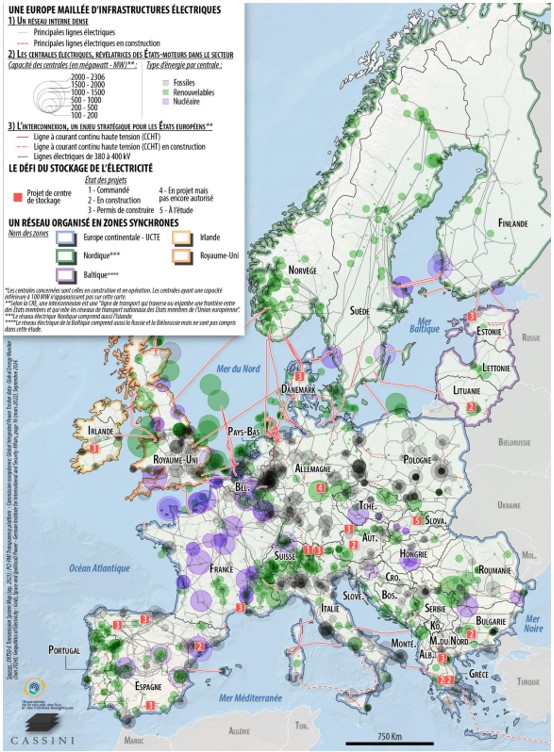

Figure 5: A connected European electricity network

Source: Cassini

Vulnerabilities of the electricity network and protection measures

Physical vulnerabilities

The end of the Cold War and the continued construction of Europe, coupled with the intent to integrate these power networks into a single market, have put their strategic nature on hold. Electricity transmission infrastructures were thus poorly protected, and the European transmission system operators (TSOS) perceived them as "normal" infrastructures, without any particular strategic dimension.

However, the physical protection of electricity transmission networks has once again become an issue. The challenges of energy transition and response to climate change have put them back under media attention and these infrastructures are sometimes subject to sabotage attempts. In addition, the risk of terrorist attacks on these infrastructures is non-negligible and the return of war on the European continent since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine creates more uncertainty on the safety of the physical network. Another crucial physical hazard that can affect these networks comes from the worsening and increasing frequency of extreme climatic events resulting from climate change.

In the EU, the (EU) 2019/941 regulation on risk preparedness in the power sector requires Member States to put in place measures to prevent, prepare for and manage possible crises affecting the electricity sector. Article 6 instructs ENTSOE to identify the most likely electricity crisis scenarios at a regional level. While ENTSO-E does not organise crisis management exercises at its level, some EU States, alone or in groups, carry out exercises at several scales, such as the members of the Pentalateral Forum3. While the technologies needed to maintain and repair these infrastructures are widely available in both hardware and software, European manufacturers and network managers are warning of "bottlenecks in terms of manufacturing capacity and qualified resources"4.

Cyberattacks

The European electricity transmission sector has opened its infrastructure to digital technology, notably to manage new renewable power production. Cybersecurity is therefore a growing concern for EU energy infrastructure. In 2023, more than 200 reported incidents targeted the energy sector and more than half of them were directed specifically against Europe, according to the European Union Agency for Cybersecurity (ENISA).

The growing interdependence between information and communication technologies and the power sector adds to its critical nature. Indeed, data-driven systems currently being built in most sectors (Internet of Things, smart cities…) depend on a continuous electricity supply. A disruption to this supply would have a major impact on society with a cascade of effects in other sectors often unprepared for this eventuality. Conversely, the decentralisation of part of the production and transmission, enabled by smart grids, allows for more network resilience.

In the context of a high-intensity conflict between Ukraine and Russia, in which the resilience of the Ukrainian electricity transmission network plays a major role and is the subject of regular strike campaigns by Russia, the pan-European Cyber Europe exercise of June 2024, organized by ENISA, focused on a scenario involving cyber threats targeting the EU energy infrastructure. The challenge for the stakeholders was to quickly coordinate their actions and their responses, particularly in their cross-border dimension.

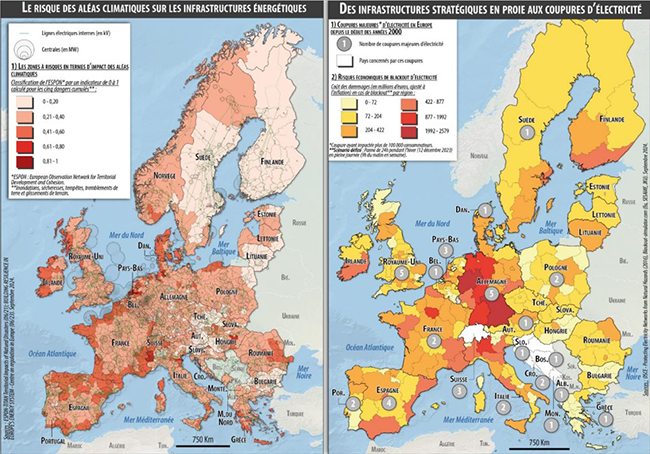

Figure 6: Vulnerabilities of the European electricity grid

Source: Cassini

To strengthen coordination at European level, essential in the event of a large-scale cyber incident, several initiatives are underway. ENTSO-E drafted a common network code on cybersecurity, which was introduced in June 2024. It aims to establish a European cybersecurity standard for cross-border electricity flows. It includes rules on cyber risk assessment, common minimum requirements, certification of cybersecurity products and services, monitoring, reporting and crisis management. Among industrial players, information sharing and analysis centres (ISACs) such as the European Energy Information Sharing & Analysis Centre are also emerging at national or European levels and are structuring information flows on the evolution of threats and the response to cyber incidents.

Economic security and foreign influence

The physical and cybernetic security of the European electricity transmission network is based on common standards and extensive information sharing between sector players. This information sharing now includes non-EU players, both due to the synchronisation of European networks with neighbouring countries and due to investments by third party countries in these networks.

The energy sector is one of the main sectors in which China invests in Europe. In 2019, the transport, energy, utilities and infrastructure sectors concentrated €800m of foreign direct investment. While these investments decreased after 2019 due to the Covid-19 pandemic, as well as because of growing tensions between China and the EU, solar photovoltaic continues to drive Chinese investment in the Union.

As part of its New Silk Roads project and its connectivity strategy, China has invested in European electricity transmission networks where possible. State Grid Corporation of China, the Chinese state monopoly on the power transmission network, has increased its stakes in European networks. This gives China visibility on the development strategy of European electricity transmission networks as well as on their vulnerabilities.

Resilience of infrastructures, markets and populations

Europe’s complex multi-scale grid resilience management

Managing the resilience of the electricity grid is particularly complex as these infrastructures, critical to national sovereignty, are the subject of European interconnection and information exchange that extends beyond its strategic alliances. This issue of resilience and its management is thus taken into account at several scales, some of which are in competition.

Within NATO, the notion of resilience is associated with Article 3 of the North Atlantic Treaty "the parties, [...] will maintain and increase their individual and collective capacity to resist an armed attack". The United States is pushing for the construction of a very broad notion of national resilience, including the entire functioning of a country's critical infrastructures but also the national cohesion of its population.

For the EU, resilience, understood in the broad sense of crisis management and resistance capacity, covers health issues, migration, infrastructure security in the face of environmental or security risks, and civil protection. In the case of electricity transmission networks, the EU takes into account cyber risks on a European scale with the “Network and Information Security” (NIS) directives, ENISA exercises and common network codes defined by ENTSO-E, whose cyber standards are currently being implemented. The security of market mechanisms is also considered on a European scale. The security of flows is constructed on an infra-regional scale, which brings together groups of neighbouring states within six regional security coordinators, while the physical security of infrastructure is taken into account on a national scale by the States.

This multiscale construction of network security implies a very high level of coordination between the different actors. The study of the Ukrainian case shows that in the case of a specific targeting of electrical infrastructures, the coordination of cyber and physical attacks is particularly effective. The United States began to practice managing this dual vulnerability in the mid-2010s through its Gridex exercises. Comparatively, the EU still lacks large-scale exercises conducted on a European scale and including several security dimensions.

European market resilience

Economic benefits and enhanced energy security result from the integration of European electricity markets, which allows for increasing synergies, particularly in the context of the energy transition and the development of renewable production. Interconnected markets can also rely on each other in the event of supply shortages or unexpected disruptions, and reduce dependence on a single energy source or supplier. However, market integration also implies that in the event of an incident, the risks of “cascade” effects and propagation between different areas increase.

The resilience of market organisations, such as electricity stock markets, lies largely in the IT security that supports the very large volume of transactions and information flows between market participants. Incidents are regularly recorded, as in the case of the market decoupling between France and Germany in June 2024. Faced with the risks of involuntary incidents and malicious actions, stock markets and other operators are seeking to increase protections and back-up solutions.

Blackout anticipation: resilience of institutions, populations, and the military

The resilience of the European electricity transmission network has continued to improve since the post-conflict reconstruction of the 1950s. The Ukrainian example also shows that even in a high-intensity conflict situation, it is difficult to bring down the entire electricity transmission infrastructure of a state on the European plate. However, while a prolonged collapse of a large part of the European electricity transmission network is a low risk, prolonged blackouts on local scales are once again becoming a proven risk. Particularly in a context of increasing extreme weather events in Europe.

This resurgence of localised power outages is accompanied by a greater vulnerability of populations. In a context where the electrification of heating (today 15% of residential heating) is growing, a large proportion European households anticipate very little, or not at all, a potential disruption in electricity supply. The preparation and resilience of the population to disruptions in electricity supply is part of a risk culture that exists in other parts of the world where environmental hazards justify it (like the US for example). This risk preparedness culture could be developed in Europe as a way to improve resilience.

A similar issue arises for the military of European States. While their energy supply is the subject of operational logistical planning, on their national territory most military bases and sites depend on the national electricity grid. Some of these sites do not possess a single injection point and share their supply with other civilian sites, which makes them difficult to identify for the network manager in the event of emergency cuts. This stresses the importance of conducting regular tests on back-up generators and associated fuel stocks. In the US, where military bases must develop electrical resilience, some have set up smart grid systems that can be activated in the event of an attack on the national grid or an extreme weather event. They allow sites to isolate themselves from the rest of the grid to operate autonomously with local renewable production and reserves for periods ranging from a few days to several weeks.

Ukraine’s power gird, a major issue in the conflict with Russia

Attacks on the Ukrainian power grid began in October 2022. Within eight days, 30% of the country's power plants were destroyed, along with many transmission lines and substations. A second wave of strikes began in September 2023. Starting from spring 2024, Russia changed its strategy: while the first two waves of strikes targeted the entire electrical system, destroying power stations and transmission lines in particular, subsequent attacks focused more on production capacities in Ukraine.

By focusing particularly on the destruction of controllable production capacities (thermal and hydraulic), Russia is undermining the flexibility of the Ukrainian network, i.e. its adaptation capacity. The Russian attacks on the network are usually combined with cyberattacks targeting power infrastructures.

Besides undermining the morale of the population, the limitations of power supply have a crucial impact on the Ukrainian economy as it relies partly on energy-intensive industrial sectors such as metallurgy. The slowdown in industrial production resulting from the lack of power supply particularly affects the Ukrainian defence industry, making the network a key strategic target for Russia. Despite these attacks, the Ukrainian power grid has managed to hold on.

To alleviate the impact of these attacks and strengthen the resilience of its grid, Ukraine has several options:

- Limiting consumption and rotating cuts to preserve supplies to critical consumers.

- Strengthening anti-aircraft defence.

- Developing decentralised production capacities.

- Facilitating the delivery of spare parts and their construction on site.

- Strengthening interconnections between the EU and Ukraine.

However, these solutions have downsides, as some of them are costly and rely heavily on outside help, while other measures might not be well accepted by the population. These measures would also have to be applied in record time, a difficult feat at a time when Ukraine is using most of its resources to fight the war.

CONCLUSION

The European electricity network has undergone significant changes over the last decades, whether in terms of infrastructure, interconnections, integration of renewable sources in transmission, production management or integration of digital technology. These changes have transformed its vulnerabilities, whether to attacks (physical or cyber) or to the growth of extreme weather events on European soil. All of this while the electricity network has now become a particularly critical infrastructure for the industrialised societies of the continent.

Strengthening the resilience of the European electricity network thus becomes a key component of European security. This need for resilience applies not only to infrastructure, but also to power markets and populations. These developments, although not entirely specific to Europe, correspond to the history of the construction of the network.

In the United States, the federal government has not sought to integrate the networks of different states into a unified system, and the federal level mainly manages interconnections between several systems with different characteristics. On the other hand, China has taken the European integration model as an example and is seeking to build a relatively unified system at the national level, supported by the development of long-distance transport technologies and the integration of renewables.

In this context of changing and increasing vulnerabilities for a European electrical architecture that could be considered unique, the example of Ukraine offers a wealth of learning opportunities. Indeed, the targeting of the Ukrainian electrical system by Russia and the means implemented by Kyiv to ensure its resilience are rich in teachings, notably for European electricity transmission network managers.

Ukraine, with the help of the EU, thus bases its electrical resilience on a mix between flexibility of network operation, the development of very technology-intensive mobile infrastructures and the preservation of an extremely rustic manual intervention capacity by teams on the ground.

Notes:

- A "synchronous" network is a network where the current has the same frequency. For the user, changing synchronous zones involves using a plug adapter to connect devices. Exchanges between non-synchronous zones require technical adaptations.

- Includes Türkiye and non-EU countries, but does not include countries from the Commonwealth of Independent States (CIS), i.e. Russia, Ukraine, Belarus, Moldova...

- Benelux, Germany, France, Austria and Switzerland.

- Future of our Grids, « Discussion and Conclusions of the High-Level Forum », 7 September 2023, Brussels. Microsoft Word - 230907_Discussions and Conclusions_Session III_FINAL2.docx

Energy and Climate Databases

Energy and Climate Databases Market Analysis

Market Analysis