While many countries move away from coal power, some are just adopting it now

This month, we look at the future of coal as an electricity source around the world, and what that means for climate change, with a brief by Professor Carine Sebi, expert on environmental economics and energy at Grenoble Ecole de Management (Grenoble Management School, or GEM), and Bruno Lapillonne, Scientific Director and co-founder of Enerdata.

What are the global trends of coal consumption in the electricity mix and what drives these trends? What are the short- and medium-term prospects, and will they support the energy transition?

According to Enerdata statistics, coal consumption1 increased at the global level in 2017, after three years of slight decrease2. This is an alarming trend, because despite increasing international awareness of the risks of global warming due to greenhouse gas emissions, some major economies are unable to substitute their coal-based electricity with less carbon-intensive energies. Indeed, coal, which is mainly used for electricity production3, generally emits twice as much CO2 as natural gas4, its main competitor.

For Two Decades, Coal Has Led Electricity Production

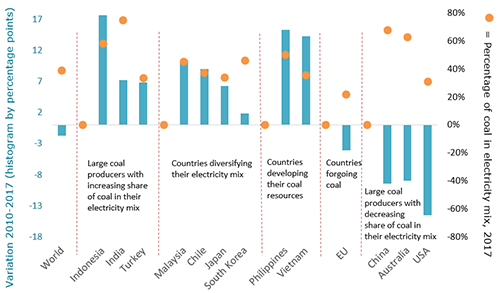

Worldwide, coal consumption for electricity generation is almost growing at the same rate as the electricity consumption (2.8%/year versus 3%/year between 2000 and 2017). As a result, the share of coal in the power mix is still around 40% and has only decreased by two-points since 2010 (Figure 1) – and coal is still the most widely used energy source for electricity generation in the world.

Figure 1 : Significant Gains in the West Almost Entirely Offset by Increasing Coal in Other Countries

Closer up, we see opposing trends in the world's largest economies: the efforts and announcements of the majority of countries that are phasing out the use of coal to produce electricity are being undermined by a number of countries that are increasing the share of coal in their power mix. This is the case particularly for major coal-producing countries such as Indonesia (58% of electricity produced from coal, +18 percentage points increase from 2010 to 2017), Turkey (33%, +7 points) and India (75%, +7 points, as shown in Figure 1, above). India is the second largest coal producer in the world after China with significant coal reserves. The development of renewables and the commissioning of more efficient coal-fired power plants in India are not sufficient to absorb the growth in electricity demand, which has averaged 7% per year since 2005.

Other countries are seeking to diversify their energy mix and are increasingly using coal to produce their electricity: Malaysia (45%, +10 points), Chile (37%, +9 points), South Korea (46%, +2 points) and Japan (33%, +6 points). These countries rely on coal for several reasons: in addition to often being a cheaper source of electricity, coal limits their dependence on oil- and gas-producing countries, and in turn limits the effect of hydrocarbon price volatility on their economies. Due to a lack of domestic fossil fuel resources, Japan is one of the largest oil-, natural gas- and coal-importing countries. Between 2011 and 2015, the share of coal in Japanese electricity production increased significantly to cope with the closure of nuclear power plants following the Fukushima accident.

Finally, some countries with national coal or lignite reserves, such as the Philippines (50%, +15 points) and Vietnam (34%, +14 points), are developing this resource to produce electricity and to improve their energy independence and balance of payment.

Conversely, the share of coal in the electricity mix has fallen sharply in most European Union countries, as well as in China and the United States. To fight climate change, EU countries are significantly reducing the use of this fuel (21%, -10 points since 2000). However, coal retains a dominant weight in the power mix of some EU coal- and lignite-producing countries, such as Poland (78%), the Czech Republic (49%) and Germany (39%), although its share in these nations is falling sharply.

China – by far the world's largest coal consumer for electricity generation – is implementing restrictive environmental and energy policies on coal use (68%, -10 points from 2000 to 2017) to improve air quality and to contribute to efforts to fight climate change.

The United States, like China, is a major coal-producing country, and has significantly reduced the importance of coal in its electricity mix (31%, -15 points) but for another reason: the development and abundance of shale gas.

Growing Capacity of Coal-fired Power Plants Worldwide

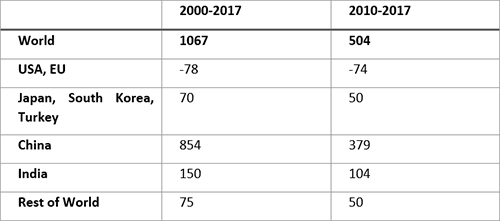

At world level, coal-fired power plant capacity has increased by 1000 GW since 2000 and by 500 GW since 2010 (Figure 1). This increase is mainly due to additions in China (+850 GW since 2000, which is 80% of the global variation) and to a lesser extent India (+150 GW since 2000). The significant decline in the United States and in the European Union (-80 GW total, or very nearly 40 GW each since 2000) was offset by increases in Japan, Korea and Turkey (+70 GW including 40 GW in Japan).

Figure 2: Variation of coal-fired power plant capacity in GW

Countries Turning Newly to Coal

What’s even more surprising in the context of widespread action to fight climate change is that some 20 countries are turning to coal (including nine in Africa, three in Central America, two in the Middle East and three in Asia). By 2025, more than 65 coal-fired power plants could be commissioned in these countries, representing a capacity of 50 GW. Most of these countries do not even have coal resources (with the exceptions of Bangladesh and Tanzania). They develop their projects mostly with Indian or Chinese funding since the major international financing agencies no longer finance this type of project.

Figure 3: Countries introducing coal-fired power plants for the first time

And in The Longer Run?

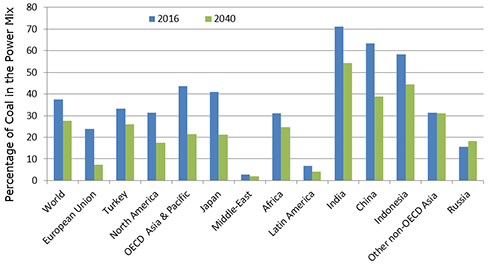

The projections of Enerdata's EnerFuture forecasts are moderately optimistic, as by 2040 the share of coal in the world power mix is expected to decrease by only 10 percentage points in the EnerBlue scenario (in which global demand increases, but demand and CO2emissions are contained within the objectives of the Paris Agreement) (see Figure 4). In line with the announcements of the “Clean Energy for All Europeans” package, the European Union, which aims for carbon neutrality by 2050, is on the right track despite Poland's reluctance to stop subsidizing its coal-fired power plants beyond 2030. China, India and Indonesia – where electricity is produced primarily from coal – will significantly reduce the share of coal in their power mix, but not below 35%, due to the abundance of domestic coal reserves and their economic attractiveness.

Figure 4: The Evolution of Coal in the Electricity Mix Speaks of Different Policies Around the World

Take-Aways

With a steady electrification increase, driven by the development of some emerging economies and the diffusion of new electric end-uses (such as e-mobility), electricity demand will continue to increase in the short and medium term. If the largest countries in the world do not put in place the solutions to substitute coal with "greener" energy, it will be exceedingly difficult to keep global warming within acceptable levels. This will require not only ceasing to build new coal power plants, but also implementing radical programs

to close the existing ones – as is already planned in most EU counties, including very recently in Germany, and notably excluding Poland. Another question mark is the impact of the plans of current US administration, which is promoting coal development by scrapping existing environment standards on coal power plants.

The challenge that remains is mainly concentrated with countries that are both large producers and consumers, such as China and India, which are trying to reduce their dependence on this mineral. But the question remains whether these efforts will be sufficient, particularly in view of the enthusiasm for coal (abundant, easy to transport and cheap) in countries currently introducing coal power generation.

1 Throughout this text, coal consumption includes lignite.

2 According to Enerdata Global Energy and CO2 Data, coal and lignite consumption increased by 0.7% in 2017 after a reduction of 1.5% per year from 2013 to 2016. This trend is confirmed by a recent report published by the International Energy Agency in December 2018.

3 Globally, two-thirds of coal is used to produce electricity (the figure becomes three-quarters when excluding China and India, where coal traditionally has a broader use. Most of what remains is used by industry, mainly to produce steel (around 50-60% of it).

4 At the same efficiency, the difference is 70%, but since gas-fired power plants are much more efficient, the difference per kWh produced is greater and reaches a factor of 2.

Energy and Climate Databases

Energy and Climate Databases Market Analysis

Market Analysis