Securing China’s energy supplies in Africa & the Belt and Road Initiative

Get this executive brief in pdf format

This article focuses on China’s energy policy, its economic diplomacy through the Belt and Road initiative, and how this shapes its relationship with the African continent. It stems from an analysis by Enerdata, the French Institute for International and Strategic Affairs (IRIS) and Cassini for the French Ministry of Defence (full report available in French here).

Introduction

After unsuccessfully trying autarky in a bid to ensure its independence and security, China opened to the world from the 1980s onwards and is now totally integrated in, and interdependent with, the global economy. Current policy is not to reconsider that interdependence, but to diminish the country’s vulnerability by securing the flows, mainly maritime, of supplies (particularly energy) and exports of the Chinese economy. For the Chinese regime, the fundamental problem is not so much China's dependence on the market as the hegemonic position of the United States (USA) on the seas, particularly around China.

It is in this context that China's relationship with the African continent should be analysed. Part of it stems from China's dependence on energy imports, due to an energy mix that is still largely dominated by hydrocarbons. But Africa is still a small player on the world oil and gas scene, and Beijing’s interest goes beyond the simple question of energy supplies and is part of a more global economic, geopolitical and strategic expansion strategy. The Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is its main instrument.

China’s energy policy

The Chinese energy policy is structured by several constraints:

- The structural increase in energy consumption. The government's response is twofold, seeking both to encourage local production (of oil, gas and renewable energy) and to reduce or at least limit consumption, notably by improving the energy efficiency of the economy.

- The need for a competitive economy. To preserve the competitiveness of its economy, China must secure its energy supply at the best price. This constraint explains the central place of coal in its energy mix: it is local, cheap, and contributes to its independence.

- The fight against global warming. China has made relatively strong commitments to limit its greenhouse gas emissions since the Paris Climate Accord resulting from COP 21 (2015), and is seeking, in parallel, to reduce air pollution, which in all the country's major urban areas far exceeds international standards. By 2050, China aims to reduce the share of fossil fuels in the country's energy mix to less than 50%.

- And the vulnerability of Chinese oil and gas supplies: securing those supplies is one of China's geopolitical priorities.

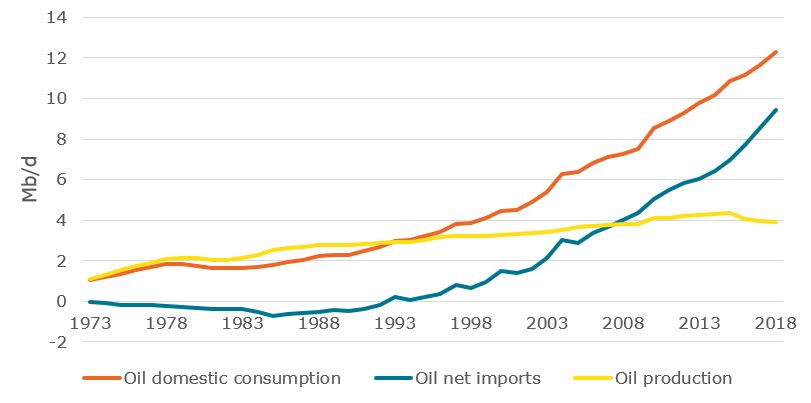

Figure 1: Production and consumption of crude oil in China 1973-2018

Source: Enerdata, Global Energy & CO2 Data

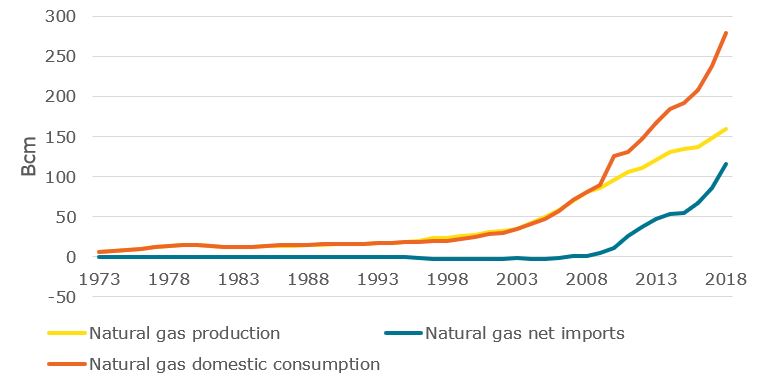

Figure 2: Production and consumption of natural gas in China 1973-2018

Source: Enerdata, Global Energy & CO2 Data

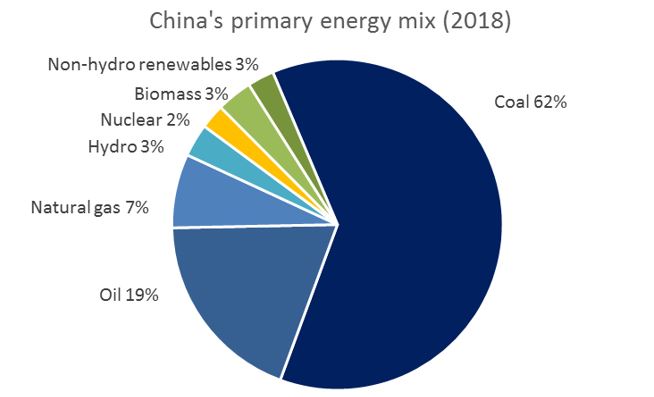

Energy Mix in China

China is since 2008 the world's largest consumer of primary energy. Its share of global primary energy consumption jumped from 8% to 22% between 1980 and 2018. It increased six-fold over the same period, to reach 3,164 million tonnes of oil equivalent (Mtoe) in 2018. China’s primary energy consumption remains dominated by coal, for which China is almost self-sufficient and which accounts for nearly 60% of its total consumption and most of its power generation. This is followed by oil (just under 20% of consumption) and natural gas (7.3%), largely dependent on imports. Nuclear and renewable energy sources (RES) see strong growth, but their share stays relatively low (2.5% in the case of nuclear, which stays below current government ambitions).

Source: Enerdata, Global Energy & CO2 Data

Tackling the oil and gas dependence

Becoming a net importer of both fuels (since 1994 for oil and 2007 for gas) has added a strategic dimension to China's oil and gas policy. China is already the largest importer of oil and gas worldwide and consumption is still rising strongly.

But this increasing dependence did not remove the competitiveness and energy transition constraints, forcing China's energy policy to articulate several, partly contradictory, objectives. To secure supplies, the government aims to:

- Diversify oil and gas sources

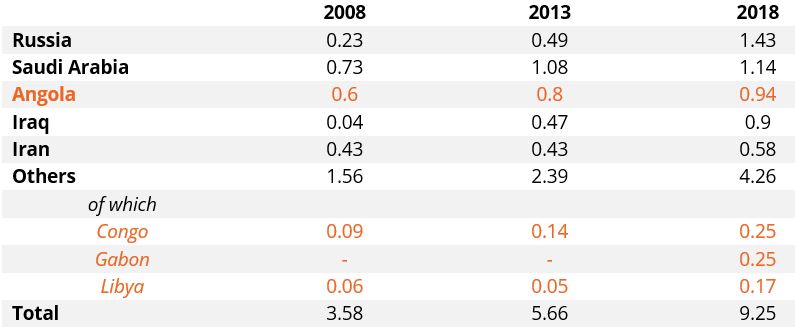

This axis aims to multiply oil and gas suppliers and reduce dependence on the Middle East. Alternatives are Central Asia, Russia, South East Asia, and Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA). In this strategy, the importance of SSA is unquestionable, particularly Angola (from where China imports nearly 1 Mb/d.) and more recently the Republic of Congo and Gabon.

Figure 3: China’s main oil suppliers vs main African suppliers (Mb/d)

Source: Middle East Economic Survey

- Diversify oil and gas import routes

The main objective is to develop terrestrial alternatives to the maritime route via the straits of Ormuz and Malacca, as the USA control the seas.

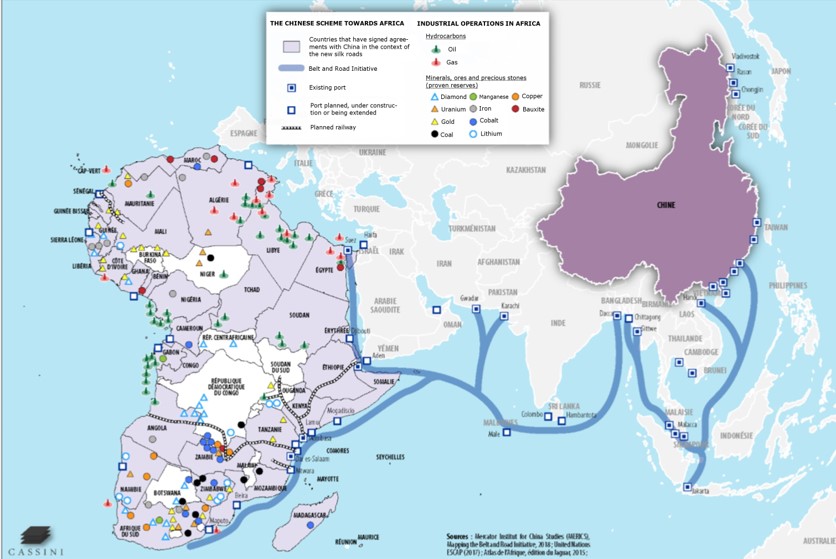

- Secure the maritime route

This axis’ objective is to secure the maritime space between the Gulf and China (South China Sea, Indian Ocean), especially the main supply route from the Persian Gulf (and Africa) via the Strait of Malacca, controlled by the US Navy. To do so, China constructed, purchased or leased on the long-term port and air facilities for its navy in most countries along the route (India excepted).

- Internationalise Chinese oil companies

The objective is to support Chinese companies abroad by granting financial loans to producing countries that welcome them. Securing the supplies is a very secondary objective, as the produced oil is sold on the market, and not necessarily to China.

Sub-Saharan Africa (SSA) occupies an important place in this strategy. It is a potential source of supply, even though African oil and gas production remains very modest compared to China's needs and the involvement of oil companies in exploration and production in Africa remains low (see below). SSA has also become, together with the Chinese base at Obock in Djibouti, one of the key anchors of China's military in the Indian Ocean. And it is one of the new areas of expansion for the international activities of Chinese companies.

The Belt and Road Initiative

This initiative was launched in 2013 as Chinese president Xi Jinping announced the double project of connecting China to Europe by land through Central Asia and thus creating a "Silk Road Economic Belt", and to develop a maritime communication route between the two continents. It has since then become the main pillar of Chinese economic diplomacy.

The official objective of the BRI is "to promote the economic prosperity of the countries along the new Silk Roads (Belt and Road), to promote regional economic cooperation, to enhance exchanges and mutual understanding among civilizations, and to promote peace and development in the world". It offers partner countries the possibility to finance and build a wide range of new infrastructure, particularly in the field of communication and transport (roads, railways, ports, airports, pipelines, internet network, etc.) and energy. Today, not only have most Asian countries and many European countries joined the initiative, but also almost the entire African continent and some Latin American countries. In addition to building infrastructure, the BRI has four other components: policy coordination, trade and investment facilitation, financial integration and cross-cultural exchanges.

Through the BRI, China is making clear its power ambitions as a global player and intends to adopt a much more proactive stance on the international stage than before. Beyond supporting the country's economic growth, giving China's national currency international stature, and strengthening energy security, it has a strong diplomatic component seen in the development of the Belt and Road International Forum and the signing of cooperation agreement with partner countries. The second forum, in May 2019, focused on the fields of energy and telecommunications. It included the signing of an agreement between the African Union and the Global Energy Internet Development Cooperation Organization, initiated by the China State Grid Corporation, the major state-owned company in charge of managing the electricity grid in China.

Africa in the BRI

Although Africa is not the centrepiece of the BRI, the continent has been attracting special attention from China for at least two decades, well before the BRI was launched. Indeed, Africa offers a range of characteristics that are perfectly in line with China's economic and strategic objectives as defined in the BRI:

- It is a continent rich in raw materials, especially oil and gas, which are essential for the functioning of the Chinese economy.

- The infrastructure needs are colossal.

- African economies, traditionally extroverted and dependent on the rest of the world (for access to finance as well as to technology and know-how), are particularly welcoming to international investors.

- Africa's population is growing much faster than anywhere else in the world, while a consumerist middle class is beginning to emerge, heralding the eventual development of a huge market.

- Political institutions are relatively weak and standards (social, environmental, safety, etc.) are low, which opens the door to low-end products and less conscientious economic players or those with less expertise.

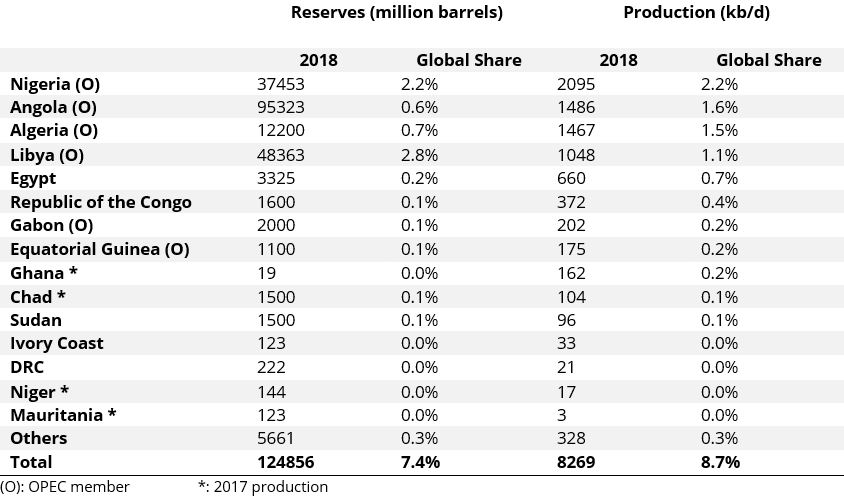

Figure 4: Reserves and production of crude oil in Africa, 2018

Source: Enerdata, Global Energy & CO2 Data

Over the last twenty years, Africa has become one of the world's most attractive oil-producing regions to foreign investors. Why? It is not so much because of the amount of oil it produces, which is insufficient to cover all of China’s needs. However:

- The continent has open and friendly contractual and tax regimes.

- Exploration techniques have improved, which has considerably expanded the areas of investigation (particularly in the deep offshore).

As a result, Africa is one of the regions of the world where production and reserves of both oil and natural gas have increased most significantly over the last two decades, thanks to the multiplication of important discoveries (the continent accounted for nearly 20% of global oil discoveries between 2011 and 2014 and for nearly 50% of gas discoveries over the 2011-2018 period).

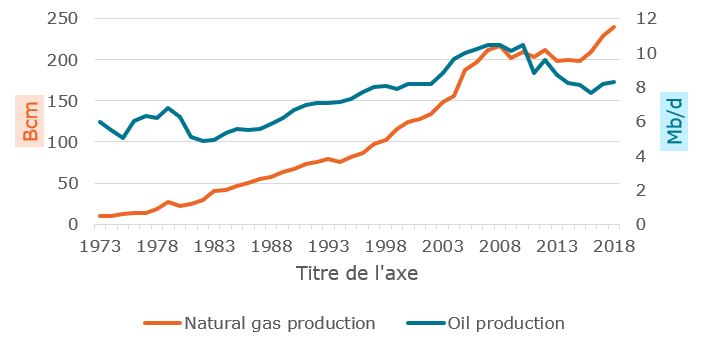

Figure 5: Evolution of the production of oil and gas in Africa 1973-2018

Source: Enerdata, Global Energy & CO2 Data

In consequence, Africa has become one of the most dynamic provinces in the world for the international oil industry. It makes it an ideal playground for Chinese oil companies such as the China National Petroleum Corp (CNPC), the China Petroleum and Chemical Corporation (SINOPEC) and the China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC).

The new strategies of China in Africa

- Commercial

China is not primarily interested in Africa for its energy and mineral resources. While those resources exist (and a part do end up in China), since they are insufficient to meet the needs of the Chinese economy, especially oil. Besides, imports from Africa are shipped by sea. Since China wishes to escape the maritime control of the United States, especially over the strait of Malacca, the African imports do nothing to bolster Chinese supply security.

However, Africa is of strategic interest as an international development field for Chinese oil companies seeking to become global players and compete (in the future) with the biggest international oil majors. The continent enables them to build up a diversified portfolio of reserves and develop their management and technological skills. Africa is also a significant market to produce Chinese goods and services (particularly in infrastructure construction).

The trade between Africa and China has seen explosive growth over the last two decades, from $10 billion in 2000 to over $200 billion in 2018, and China has become the continent's largest trading partner. The trade balance with China was generally favourable to Africa until 2012, but it has since been marked by large trade deficits ($46 billion in 2016, equivalent to Africa's trade deficit with the rest of the world, while the volume of Africa's trade with China was only 15% of Africa's total trade with the rest of the world).

- Financial

China is not a major investor in Africa, contrary to popular belief. Chinese FDIs to Africa represents only 1.2% of China's total FDIs in the world and tend to decline in absolute terms. China finances and builds infrastructure in Africa and is more of a creditor and service provider than an investor, while Africa is more of a customer than a partner. In the end, African countries pay for these infrastructures themselves by indebting themselves to China.

Most of the infrastructure construction projects carried out by China in African countries are handled by the China Development Bank (CDB), China Exim Bank and Sinosure, which arrange financing, obtain export credit insurance and bring in Chinese service providers. The banks practice tied lending, making the loans conditional to the use of Chinese contractors to build the infrastructures. The Chinese government thus indirectly supports the internationalisation of its companies by guaranteeing them contracts with the countries assisted. In some cases, e.g. the loans to Angola in the 2000s, raw materials (such as oil fields) or infrastructure have been used as collateral.

- Diplomatic

The BRI is also a way for China to increase its circle of friends. Over a hundred countries are supporting the initiative. And China is reaping geopolitical advantages: only one country in Africa (Eswatini) still recognises Taiwan, though it used to have strong diplomatic ties on the continent. Most African countries are also implicitly aligned behind China in its trade war against the United States.

To secure its long-term hold on the African continent, China also set up in 2000 the Forum on China-Africa Cooperation (FOCAC). It has become, over the years, a real instrument for the implementation of the Sino-African roadmap, in terms of development, investment and "South-South dialogue", disconnected from the Western diplomatic orbit. At the last forum, held in Beijing in September 2018, aid amounting to $60 billion for Africa was announced.

- Security

The BRI consolidates China’s international stature and justifies an increased military presence abroad and the establishment of new military bases, in addition to military cooperation with host countries. Beijing is also training local security forces and increasingly providing technology to build local capacity for intelligence gathering, surveillance, monitoring and response.

Key take-aways

- China needs to import more and more oil and gas to fuel its economic growth in a context of limited domestic production.

- This creates vulnerabilities:

- on the supply side, China seeks to diversify its sources;

- on the transport side, as the main import route is maritime, and the US navy has effective control of the seas.

- To tackle these issues, China launched the Belt and Road Initiative, which has become the main pillar of its economic diplomacy.

- Africa plays an important role within this initiative:

- partly for its energy resources;

- as an important trading partner;

- to develop the international exposure of Chinese oil companies;

- as a support base for Chinese military presence abroad;

- to secure allies on the international scene.

Figure 6: Chinese ambitions in Africa

Source: Cassini

Energy and Climate Databases

Energy and Climate Databases Market Analysis

Market Analysis