Mixed impacts in the short term

Get this executive brief in pdf format

A high-share of fossil fuel in the energy mix is not only a burden regarding greenhouse gases emissions but also in terms of security of supply. With limited and depleting resources, the EU experiences extremely high dependency rates, at 95% for oil (relatively stable) and at 85% for gas (+15% over the past decade)1. The recent succession of crises (Covid-19, surge in gas and electricity prices in 2021, Ukrainian crisis in 2022) is an implacable reminder that long term climate objectives cannot be achieved without addressing, in parallel, the issues of energy security and affordability. These three topics are the pillars of the EU’s energy strategy. This executive brief explores how energy transition in the EU could be impacted by these recent crises in the short term, through the lens of the latest trends in fossil fuel consumption.

The EU’s energy consumption is dominated by oil and gas

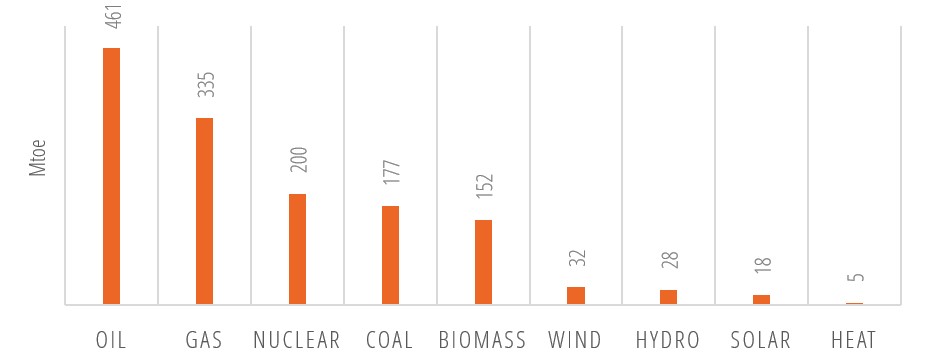

In 2019, before the Covid-19 crisis, oil was by far the most consumed energy source in the EU (Figure 1): it accounted for one third of total energy consumption, followed by gas (24% of total consumption). At world level we observe the same shares for oil and gas. The main difference comes from a lower dependency on coal at EU level (13% share in EU vs. 27% globally) with an acceleration of coal phase out since 2015. This is balanced with a higher share of nuclear in the EU globally (14% vs. 5%).

Figure 1: EU primary energy consumption per fuel, 2019 (pre-Covid level)

Source: Enerdata, Global Energy and CO2 Data

Oil consumption was hit by the recent crisis, but short-term measures to limit the surge in oil prices could delay the transition to decarbonised transportation

Transportation and more precisely road transportation drive oil consumption with respectively 70% and 60% share in final oil energy consumption in EU2. The pandemic has deeply impacted the transportation sector with lockdowns, remote work slightly reduced freight transportation but also aviation, with strict prophylactic measures. In 2021 total oil demand rebounded by 5% in the EU (following an 8% drop in 2020) mainly driven by the rebound in economic activity (GDP increased by 5.3% in 2021 vs. 5.9% drop in 20203):

- The road freight activity remains below pre-Covid-19 level despite the growth in retail and e-commerce, and a more limited rebound in industrial sectors such as construction.

- Covid-19 could have a limited (less than 1% of total oil demand) but long-lasting impact on passenger transportation with up to 40% of jobs that are suitable for teleworking in OECD countries4.

- Aviation is not expected to return to its 2019 consumption level before 2023 in Europe and business travel could remain below pre-Covid-19 levels in the mid-term.

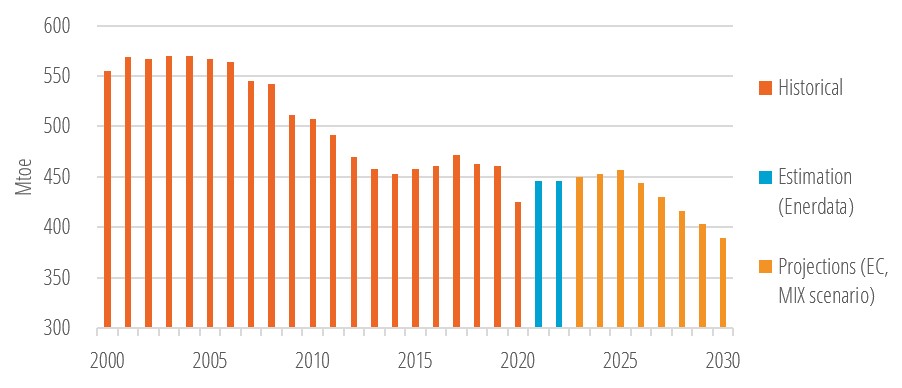

Figure 2: Oil consumption, EU

Source: Enerdata, Global Energy and CO2 Data, EnerMonthly and EC, European Commission5

The EU started 2022 with the Ukrainian crisis which has strong impacts on energy markets. Oil prices are reaching record elevated levels and, more generally, the surge in energy prices that started in 2021 is a key driver pushing inflation to unprecedented levels in the past decade. Consequences on economic activity6 and purchasing power will limit or cancel out the growth in oil demand for 2022. In terms of security of supply, Ukrainian crisis and dependency on Russian oil imports have a limited impact (especially compared to gas) on the EU due to the nature of oil market both liquid and global.

Figure 3: Brent spot price and Natural gas TTF spot price

Source: Energymarketprice

In the meantime, at the beginning of the pandemic, the European Green Deal was presented and more recently, in July 2021, the "Fit for 55" Package was launched by the European Commission. To which extent the legislation proposals and climate objectives of these plans have been affected by the current crisis?

The "Fit for 55" Package includes measures that directly address oil consumption and road transportation, for instance: development of a new emission trading system for buildings and road transportation, development of alternative fuels infrastructure, ban of internal combustion engine cars or vans by 2035. The recent crises emphasise the need for the EU to decrease its dependency on fossil fuel imports and among the measures put in place to face high energy prices and dependency to Russian oil and gas imports, only a few have a direct positive impact on energy transition. The REPowerEU plan communicated by the European Commission on March 8th mentions the option to boost the Fit for 55 proposals with higher or earlier targets but so far, the only short-term measure with co-benefits on climate is an incentive to turn down the thermostat for buildings’ heating by 1°C. In parallel most Member States have implemented short term measures to shield consumers from the direct impact of rising prices. In the case of oil and gas this can be considered as direct support or subsidies to fossil fuel which could delay the transition to alternative fuels.

Natural gas: from a transition fuel to a threat in security of supply

The EU’s natural gas total consumption reached 412 bcm in 20197 before the start of the pandemic. The energy sector (mainly power plants) and buildings account for almost ¾ of total consumption with respective shares of 37% and 35%. The share of industry is slightly below ¼ of total consumption.

Besides the power sector, natural gas uses are driven by space-heating in buildings and industrial consumption:

In the short-term, space-heating is very dependent on climatic conditions; in the longer term, it is driven by energy efficiency improvements, switch to heat pumps, buildings insulation and gas prices

Industry consumption is driven by global economic activity, gas price and CO2 price and in the longer term by energy efficiency improvements and a switch to decarbonated processes.

Figure 4: Natural gas consumption, EU

Source: Enerdata, Global Energy and CO2 Data

Overall, Covid-19 had a limited direct impact on natural gas consumption; the drop in economic activity in 2020 led to 3% decrease in industry consumption8 whereas buildings consumption variation is more dependent on temperature and space heating needs. However, the economic rebound in 2021 was a key factor that triggered a surge in gas prices which, in return, impacted natural gas demand.

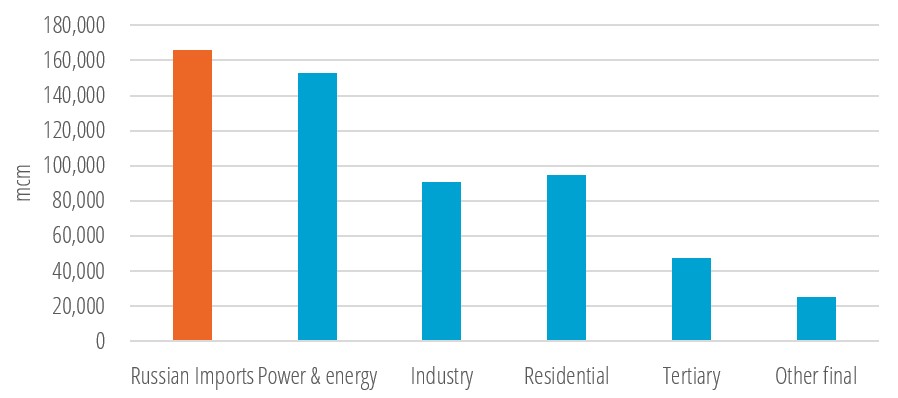

The Ukrainian crisis amplified the explosion of natural gas prices and added a security of supply crisis. With more than 150 bcm, Russian imports account for almost 40% of total annual natural gas imports, which is roughly equivalent to the gas consumption of the EU power sector9. The uncertainty around the role of natural gas in the EU’s energy system is rising in early February natural gas was labelled as a transition fuel in the EU taxonomy and a few weeks later the European Commission presented in its REPowerEU plan options to decrease dependency on Russian imports and more generally on natural gas.

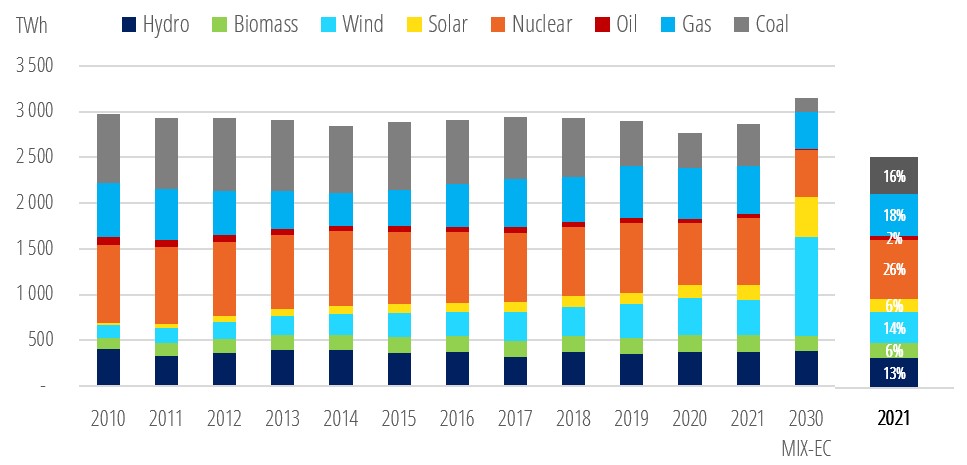

The main challenges of natural gas posed by recent crises and energy transition lays on the EU’s power sector. With around 20% of power generation (Figure 5), gas-fired power plants play a key role in the power mix and offer flexibility to balance the grid. It is a dispatchable technology with relatively high short term marginal costs. The main drivers of natural gas power generation in the short term depend on the general electricity supply/demand balance and the relative competitivity against other dispatchable technologies.

The recent crises impacted several of these drivers, which has resulted in a decrease in natural gas power generation in both 2020 and 2021 (Figure 5). In 2020 this decrease was a direct consequence of the pandemic that hit global economy and electricity demand. In 2021 it is mainly linked to a switch to coal power generation due to the deterioration of gas-fired power plant competitiveness with skyrocketing natural gas price, despite the economic recovery and a lower wind output. The Ukrainian crisis has reinforced the pressure on natural gas price: future gas prices indicate that this situation could extend beyond 2024.

Figure 5: EU power generation mix

Source: Enerdata, Global Energy and CO2 Data, calculations from Eurostat, European Commission

The consequences on the decarbonisation of the EU power mix are unclear. In the long term, the role of natural gas in the power mix could be reduced compared to existing plan and scenarios.

In the short and mid-term, high electricity prices could lower electricity demand and indirectly dispatchable power generation including gas and coal. High natural gas prices could have a positive impact on the CO2 intensity of the power mix, and dependency on fossil fuel imports with a boosted deployment of renewables which would be more competitive. However, it could cancel out by a slowdown in coal phase out due to lower marginal production cost for coal vs. gas fired power plants.

Coal phase out: a persistent slow-down?

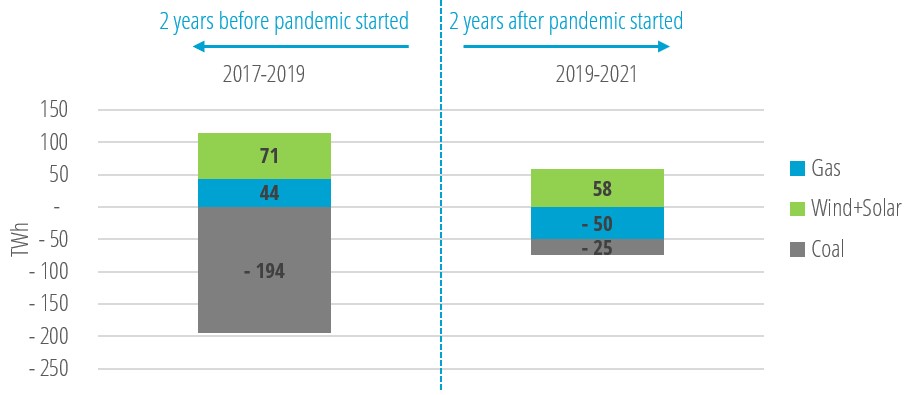

A focus on the two years that follow the start of the pandemic shows that the growth in solar+wind power generation roughly balance the decrease in gas power generation (Figure 6). However, the two years that precede tell another story:

- Coal phase out required much more than the additional solar+wind additional power generation to be cancelled out in 2018 and 2019. After the Covid-19 outbreak, coal phase out has almost stopped compared to the previous period. And if we look more closely to 2021 and the partial recovery from the pandemic, we observe that the increase in coal power generation (+20%) more than offsets the drop in gas power generation to support the rebound in electricity demand.

Growth in solar+wind power generation has slightly slowed down after Covid-19 outbreak mainly due to poor wind conditions.

Figure 6: EU power generation variation

Source: Enerdata, calculations from Global Energy & CO2 Data

Understanding the impact of Covid-19, the Ukrainian crisis, and the surge in energy prices on the future of the EU power mix requires to sort out structural trends and conjunctural factors.

Skyrocketing energy prices are the main conjunctural driver. Fuelled by the economic recovery (temporary by nature) and the Ukrainian crisis, it is expected to extend up to 2024-2025 by looking at current future prices. It is possible to anticipate and already observe some consequences:

- Coal power generation is more competitive than gas, despite relatively high CO2 prices;

- High fossil fuel prices could boost renewable penetration in the mid-long term with revised objectives;

- High electricity prices could negatively impact electricity demand, especially industry and worsen EU economic competitivity. In the long-term it could accelerate efforts in energy efficiency

The dependency on Russian gas is a more structural driver and the Ukrainian crisis raised awareness in the harsh way. Several plans were set up to drastically reduce natural gas imports from Russia. In terms of natural gas end-uses the main options are sufficiency (decrease thermostat temperature), energy efficiency and electrification (REPowerEU plan from the European Commission) or switch from natural gas inputs in the power system (IEA 10 points plan10). Several EU Member States mentioned explicitly the option to delay in the short-term coal phase out (including Germany and Italy). However, in the short-term switch from gas to coal could have a limited impact in terms of carbon budget since these emissions are covered by the EU Emission Trading Scheme.

In the longer term, structural changes of the EU power mix do not seem to be impacted by recent crises and so far, we have not observed adjustments in long term coal phase out policies. Overall, coal’s comeback in EU power mix is not good news and points out a structural weakness (dependency to Russian gas) but it could be just a simple temporary option. The role of natural gas in the power mix as a transition fuel could be questioned, depending on how fast EU natural gas supply can be diversified and how fast renewables can ramp up.

Key take aways

General post-Covid economic and energy/climate context:

- The EU’s energy consumption is still dominated by oil and gas. Transportation and more precisely road transportation drive oil demand, with respectively 70% and 60% share in final oil energy consumption in EU.

- The EU’s natural gas total demand reached 412 bcm in 2019 before the start of the pandemic. The energy sector (mainly power plants) and buildings account for almost ¾ of total consumption with respectively a share of 37% and 35%. The share of industry is slightly below ¼ of total consumption.

- In recent pre-Covid-19 years, the COP decarbonisation objectives were far from being reached and the CO2 emissions mitigation observed during pandemic years (2020-2021) was, as it turned out, mostly (if not only) due to lockdown measures. As an order of magnitude, the global drop in CO2 emissions in 2020 is roughly what would be required annually to be on track with Paris Agreement.

- The strong post-pandemic growth automatically resulted in a surge in emissions (notably in the industry and transport sectors) due to the catch-up effect, i.e., the appetite for goods and leisure (fuelled by Covid stimulus policies and resulting consumer savings)

- This economic situation led to inflation rates that had not been seen for decades in western countries. in particular, energy prices rose sharply.

- Oil consumption was hit by recent crises but short-term measures to limit the surge in oil prices could delay the transition to decarbonised transportation.

Short/Mid-term consequences of the Ukraine situation:

- On the one hand, the resulting economic slowdown that some European countries are currently facing will undoubtedly help cutting down emissions over the next few months.

- The current uncertainty regarding natural gas supply (which is not due to vanish in the coming months, let alone future measure that may be taken by the EU), led some countries (e.g., Germany) to significantly speed up their new renewables capacities roll-out planning.

- On the other hand, the role of natural gas in the power mix as a transition fuel could be questioned, depending on how fast EU natural gas supply can be diversified.

- The Ukrainian crisis has reinforced the pressure on natural gas price: future gas prices indicate that this situation could extend beyond 2024.

- As a result, there are good reasons to believe that the power generation coal phase-out will be delayed by a few years. Coal’s comeback in EU power mix is not good news and points out a structural weakness (dependency to Russian gas) but it could be just a simple temporary option.

In the end, as some of those positive and negative consequences (in terms of climate) will even out, times of uncertainties do not favour structural changes. Moreover, since solar panels and hydrogen trucks cannot be massively deployed overnight, the required emissions mitigations in the short-run to meet climate targets are not to be expected over the next couple of years but recent crises could boost decarbonisation plans in the longer term.

Notes:

- Enerdata, Global Energy and CO2 Data

- Enerdata, Global Energy and CO2 Data

- Eurostat

- IEA, Oil 2021 report

- The MIX scenario reaches -55% emissions reduction by 2030 by combining some intensification of the policies and extending the carbon pricing to buildings and road transport.

- EU GDP growth forecast for 2022 reaches 2.9% in IMF April estimates vs. 4% in January pre-war estimate

- Enerdata, Global Energy and CO2 Data

- Enerdata, Global Energy and CO2 Data

- Enerdata, Global Energy and CO2 Data

- https://www.iea.org/reports/a-10-point-plan-to-reduce-the-european-unio…

Energy and Climate Databases

Energy and Climate Databases Market Analysis

Market Analysis